Een nieuw bewustzijn binnen de wetten van de dialectiek

The dissolution of Western classical culture is a phenomenon that can be understood only against the background of a social evolution which can end only in the total collapse of a principle of society thousands of years old and its replacement by a system whose laws are based on the immediate demands of human vitality. The influence the ruling classes have wielded over the creative consciousness in history has reduced art to an increasingly dependent position, until finally the real psychic function of that art was attainable only for a few spirits of genius who in their frustration and after a long struggle were able to break out of the conventions of form and rediscover the basic principles of all creative activity.

Together with the class society from which it emerged, this culture of the individual is faced by destruction too, as the former’s institutions, kept alive artificially, offer no further opportunities for the creative imagination and only impede the free expression of human vitality. All the isms so typical of the last fifty years of art history represent so many attempts to bring new life to this culture and to adapt its aesthetic to the barren ground of its social environment. Modern art, suffering from a permanent tendency to the constructive, an obsession with objectivity (brought on by the disease that has destroyed our speculative-idealizing culture), stands isolated and powerless in a society which seems bent on its own destruction. As the extension of a style created for a social élite, with the disappearance of that élite modern art has lost its social justification and is confronted only by the criticism formulated by a clique of its connoisseurs and amateurs.

Western art, once the celebrator of emperors and popes, turned to serve the newly powerful bourgeoisie, becoming an instrument of the glorification of bourgeois ideals. Now that these ideals have become a fiction with the disappearance of their economic base, a new era is upon us, in which the whole matrix of cultural conventions loses its significance and a new freedom can be won from the most primary source of life. But, just as with a social revolution, this spiritual revolution cannot be enacted without conflict. Stubbornly the bourgeois mind clutches onto its aesthetic ideal and in a last, desperate effort employs all its wiles to convert the indifferent masses to the same belief. Taking advantage of the general lack of interest, suggestions are made of a special social need for what is referred to as ‘an ideal of beauty’, all designed to prevent the flowering of a new, conflicting sense of beauty which emerges from the vital emotions.

As early as the end of the First World War the DADA movement tried by violent means to break away from the old ideal of beauty. Although this movement concentrated increasingly on the political arena, as the artists involved perceived that their struggle for freedom brought them into conflict with the laws that formed the very foundations of society, the vital power released by this confrontation also stimulated the birth of a new artistic vision.

In 1924 the Surrealist Manifesto appeared, revealing a hitherto hidden creative impulse – it seemed that a new source of inspiration had been discovered. But BRETON’s movement suffocated in its own intellectualism, without ever converting its basic principle into a tangible value. For Surrealism was an art of ideas and as such also infected by the disease of past class culture, while the movement failed to destroy the values this culture proclaimed in its own justification.

It is precisely this act of destruction that forms the key to the liberation of the human spirit from passivity. It is the basic pre-condition for the flowering of a people’s art that encompasses everyone. The general social impotence, the passivity of the masses, are an indication of the brakes that cultural norms apply to the natural expression of the forces of life. For the satisfaction of this primitive need for vital expression is the driving force of life, the cure for every form of vital weakness. It transforms art into a power for spiritual health. As such it is the property of all and for this reason every limitation that reduces art to the preserve of a small group of specialists, connoisseurs and virtuosi must be removed.

But this people’s art is not an art that necessarily conforms to the norms set by the people, for they expect what they were brought up with, unless they have had the opportunity to experience something different. In other words, unless the people themselves are actively involved in the making of art. A people’s art is a form of expression nourished only by a natural and therefore general urge to expression. Instead of solving problems posed by some preconceived aesthetic ideal, this art recognizes only the norms of expressivity, spontaneously directed by its own intuition. The great value of a people’s art is that, precisely because it is the form of expression of the untrained, the greatest possible latitude is given to the unconscious, thereby opening up ever wider perspectives for the comprehension of the secret of life. In the art of genius, too, Western classical culture has recognized the value of the unconscious, for it was the unconscious which made possible a partial liberation from the conventions which bound art. But this could be achieved only after a long, personal process of development, and was always seen as revolutionary. The cycle of revolutionary deeds which we call the evolution of art has now entered its last phase: the loosening of stylistic conventions. Already weakened by Impressionism, laid bare by Cubism (and later by Constructivism and Neo-Plasticism), it signifies the end of art as a force of aesthetic idealism on a higher plane than life. What we call ‘genius’ is nothing else but the power of the individual to free himself from the ruling aesthetic and place himself above it. As this aesthetic loses its stranglehold, and with the disappearance of the exceptional personal performance, ‘genius’ will become public property and the word ‘art’ will acquire a completely new meaning. That is not to say that the expression of all people will take on a similar, generalized value, but that everyone will be able to express himself because the genius of the people, a fountain in which everyone can bathe, replaces the individual performance.

In this period of change, the role of the creative artist can only be that of the revolutionary: it is his duty to destroy the last remnants of an empty, irksome aesthetic, arousing the creative instincts still slumbering unconscious in the human mind. The masses, brought up with aesthetic conventions imposed from without, are as yet unaware of their creative potential. This will be stimulated by an art which does not define but suggests, by the arousal of associations and the speculations which come forth from them, creating a new and fantastic way of seeing. The onlooker’s creative ability (inherent to human nature) will bring this new way of seeing within everyone’s reach once aesthetic conventions cease to hinder the working of the unconscious.

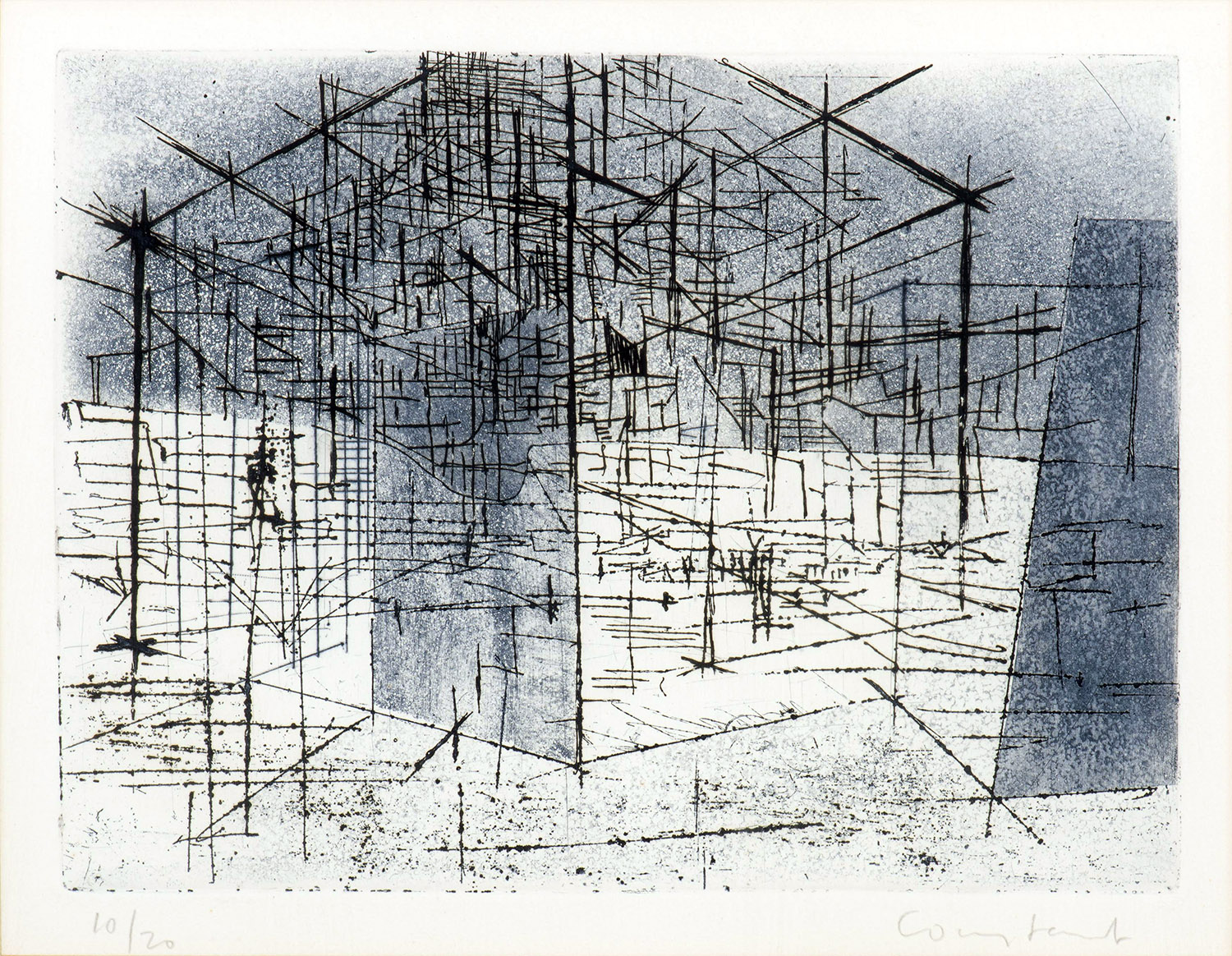

Hitherto condemned to a purely passive role in our culture, the onlooker will himself become involved in the creative process. The interaction between creator and observer makes art of this kind a powerful stimulator in the birth of the creativity of the people. The ever greater dissolution and ever more overt impotence of our culture makes the struggle of today’s creative artists easier than their predecessors – time is on their side. The phenomenon of ‘kitsch’ has spread so quickly that today it overshadows more cultivated forms of expression, or else is so intimately interwoven with them that a demarcation line is difficult to draw. Thanks to these developments, the power of the old ideals of beauty is doomed to decay and eventually disappear and a new artistic principle, now coming into being, will automatically replace them. This new principle is based on the total influence of matter on the creative spirit. This creative concept is not one of theories or forms, which could be described as solidified matter, but arises from the confrontation between the human spirit and raw materials that suggest forms and ideas.

Every definition of form restricts the material effect and with it the suggestion it projects. Suggestive art is materialistic art because only matter stimulates creative activity, while the more perfectly defined the form, the less active is the onlooker. Because we see the activation of the urge to create as art’s most important task, in the coming period we will strive for the greatest possible materialistic and therefore greatest possible suggestive effect. Viewed in this light, the creative act is more important than that which it creates, while the latter will gain in significance the more it reveals the work which brought it into being and the less it appears as a polished end-product. The illusion has been shattered that a work of art has a fixed value: its value is dependent on the creative ability of the onlooker, which in turn is stimulated by the suggestions the work of art arouses. Only living art can activate the creative spirit, and only living art is of general significance. For only living art gives expression to the emotions, yearnings, reactions and ambitions which as a result of society’s shortcomings we all share.

A living art makes no distinctions between beautiful and ugly because it sets no aesthetic norms. The ugly which in the art of past centuries has come to supplement the beautiful is a permanent complaint against the unnatural class society and its aesthetic of virtuosity; it is a demonstration of the retarding and limiting influence of this aesthetic on the natural urge to create. If we observe forms of expression that include every stage of human life, for example that of a child (who has yet to be socially integrated), then we no longer find this distinction. The child knows of no law other than its spontaneous sensation of life and feels no need to express anything else. The same is true of primitive cultures, which is why they are so attractive to today’s human beings, forced to live in a morbid atmosphere of unreality, lies and infertility. A new freedom is coming into being which will enable human beings to express themselves in accordance with their instincts. This change will deprive the artist of his special position and meet with stubborn resistance. For, as his individually won freedom becomes the possession of all, the artist’s entire individual and social status will be undermined.

Our art is the art of a revolutionary period, simultaneously the reaction of a world going under and the herald of a new era. For this reason it does not conform to the ideals of the first, while those of the second have yet to be formulated. But it is the expression of a life force that is all the stronger for being resisted, and of considerable psychological significance in the struggle to establish a new society. The spirit of the bourgeoisie still permeates all areas of life, and now and then it even pretends to bring art to the people (a special people, that is, set to its hand).

But this art is too stale to serve as a drug any longer. The chalkings on pavements and walls clearly show that human beings were born to manifest themselves; now the struggle is in full swing against the power that would force them into the straitjacket of clerk or commoner and deprive them of this first vital need. A painting is not a composition of colour and line but an animal, a night, a scream, a human being, or all of these things together. The objective, abstract spirit of the bourgeois world has reduced the painting to the means which brought it into being; the creative imagination, however, seeks to recognize every form and even in the sterile environment of the abstract it has created a new relationship with reality, turning on the suggestive power which every natural or artificial form possesses for the active onlooker. This suggestive power knows no limits and so one can say that after a period in which it meant NOTHING, art has now entered an era in which it means EVERYTHING.

The cultural vacuum has never been so strong or so widespread as after the last war, when the continuity of centuries of cultural evolution was broken by a single jerk of the string. The Surrealists, who in their rejection of the cultural order threw artistic expression overboard, experienced the disillusionment and bitterness of talent become useless in a destructive campaign against art, against a society which, though they recognized its responsibility, was still strong enough to be considered as theirs. However, painters after the Second World War see themselves confronted by a world of stage decors and false façades in which all lines of communication have been cut and all belief has vanished. The total lack of a future as a continuation of this world makes constructive thought impossible. Their only salvation is to turn their backs on the entire culture (including modern negativism, Surrealism and Existentialism). In this process of liberation it becomes increasingly apparent that this culture, unable to make artistic expression possible, can only make it impossible. The materialism of these painters did not lead, as bourgeois idealists had warned, to a spiritual void (like their own?), nor to creative impotence. On the contrary, for the first time every faculty of the human spirit was activated in a fertile relationship with matter. At the same time a process was started in which ties and specific cultural forms, which in this phase still played a role, were naturally thrown off, just as they were in other areas of life.

The problematic phase in the evolution of modern art has come to an end and is being followed by an experimental period. In other words, from the experience gained in this state of unlimited freedom, the rules are being formulated which will govern the new form of creativity. Come into being more or less unawares, in line with the laws of dialectics a new consciousness will follow.

Constant